The Global Development Assistance (GDA) programme was created in 2019 by ESA member states to fuel and boost cooperation with International Financial Institutions (IFIs). GDA aims at mainstreaming Earth Observation (EO) information into development operations and financing, by demonstrating the benefits and value of EO data to those IFIs and their client governments in developing countries. GDA and the overarching cooperation framework – Space for International Development Assistance (Space for IDA) – are implemented in collaboration with key multilateral IFIs namely the World Bank (WB) and the Asian Development Bank (ADB) in the initial phase. Further IFIs have expressed interest to partner with GDA following the Space for IDA cooperation principles, with the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) most recently joining as associate partner via a dedicated commitment to programmatic alignment and strengthened institutional cooperation. Other IFIs such as the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) and African Development Bank (AfDB) are expected to follow a similar path. These IFIs are important players in the international development landscape, since they extend development assistance directly to government entities in low- and middle-income countries, using a range of financing instruments.

In mid-2022, under the GDA Monitoring and Evaluation and Impact Assessment activity (M&E), Caribou Space carried out an analysis of the development landscape within which the GDA programme was launched. The analysis profiled the key players in the international development sector, the strategic priorities of the main funding countries and the general trends in the bilateral and multilateral funding flows of Official Development Assistance (ODA). As GDA approaches the end of its second full year of implementation, we reflect on two of the key trends that are shaping the development landscape and consider their potential implications for the GDA programme and the Space for IDA cooperation framework.

New funders on the block

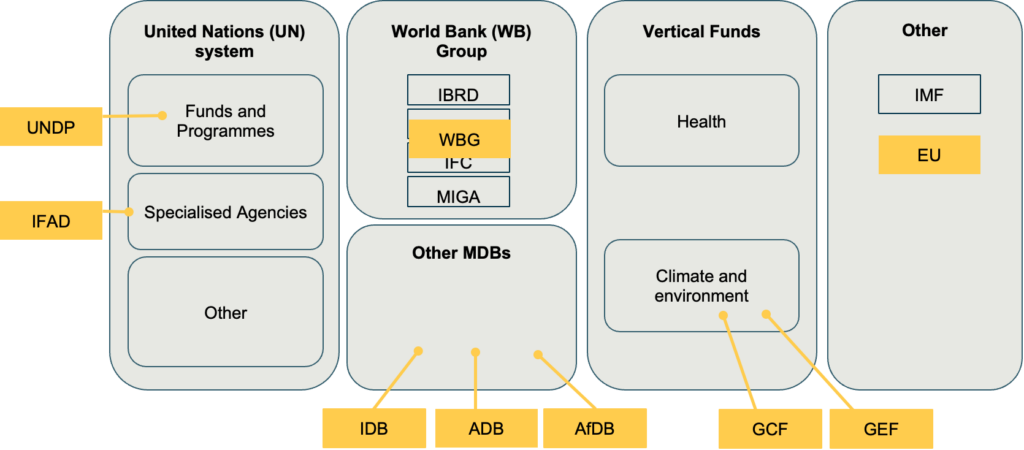

The multilateral system was established around 75 years ago and comprises the United Nations system, the World Bank Group, the regional Multinational Development Banks (MDBs) such as ADB as well as other institutions or ‘communities’ such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the European Union. Traditionally, these multilateral institutions solicit funding from country level donors and then implement projects with country government counterparts, using a variety of funding instruments including loans, grants, technical assistance and blended finance. IFI Trust Funds and Programmes explicitly forbid donor ‘earmarking’, but donors are still able to state a preference for how their contributions are allocated and so funding decisions risk being politically motivated and administratively burdensome.

Figure 1: The Multilateral System today (author’s own analysis. Note: this is not an exhaustive representation, only selected examples are shown here)

Over the past two decades or so, there has been a trend towards the establishment of so-called ‘vertical funds’ which pool and then channel donor resources to specific strategic issues particularly in the areas of global health and climate financing. These funds bring together private and public resources and enable a direct and coordinated response to be made to big global challenges and have their own governance structures, financing mechanisms and modes of engaging with operational partners in country. These structures were designed to streamline funding decisions, accelerate progress in specific global challenge areas and allow for more transparency on funding decisions and outcomes achieved. Vertical Funds aim to work in close partnership with country governments and agencies, increasing country-level ownership of the management of these significant challenges. They are also designed to respond more rapidly to emerging crises or challenges, with nimble decision-making processes and flexible financing mechanisms.

The growing importance of vertical funds in domain areas such as climate resilience and environment issues, is of high relevance to the stakeholders and industry partners involved in GDA. As a trustee for a number of vertical funds including the Global Environment Facility, the Climate Investment Funds, the Adaptation Fund and the Green Climate Fund, the World Bank will continue to navigate the funding landscape and to identify ways to collaborate with, and amplify the work of, the vertical funds and their operations in country. It will be important to ensure coordination between efforts and avoid duplication in order to maximise the combined impacts of both streams of financing. GDA is active in a number of thematic areas where the involvement of vertical funds is already high. For example, in GDA AID Marine, the PROCARIBE project receives GEF funding and in the Dominican Republic we are working with the IADB on a CIF-funded initiative. GDA is also leveraging GEF and CIF funding in the GDA AID Climate Resilience activity.

As GDA continues, we will continue to identify the best levers for mainstreaming the use of EO in-country and the optimal modes of engagement for in-country agencies and partners.

‘Hot topics’ in the development landscape

Another important trend that it will be worth monitoring over the course of the GDA programme is the growing attention placed by donors on the process of digital transformation, digital data and the emergence of the ‘digital public goods’ agenda.[1] Many donors are becoming increasingly interested in these agendas and are channelling more funding towards initiatives that promote digital economies and leverage public investment into enabling digital public infrastructure, digital skills and e-government or e-services. And the economic rationale for this seems clear. As a recent report from London Economics and Caribou Digital pointed out, a US$1 investment in digital capabilities, such as EO, can result in wider economic benefits of up to US$20 for society. Europe’s Copernicus programme is a compelling example of a digital public good investment which can be leveraged to deliver insights and tools to support decision making globally.

There are several potential implications of this for the GDA programme and the Space for IDA cooperation framework:

- GDA should leverage complementary investments into digital and data capability. In recognition of the need to adapt to the Digital Age, there may be increasing investment into building digital skills in low- and middle-income economies and in establishing the digital and spatial data infrastructure that will enable governments and societies to derive maximum benefit from livelihoods, products and services in the Digital Age. The WB’s Digital Earth Partnership is focusing on the digital skills agenda via the Resilience Academy approach. GDA is and will remain engaged in these and other complementary capacity building and skills transfer activities across the IFIs in order to ensure full alignment with them and to avoid a duplication of effort.

- GDA can demonstrate the viability and added value of commercial, bespoke solutions: In the context of donor and public support for open-source software, the GDA programme can demonstrate a rationale for the development of customised and commercial services to meet specific user needs. GDA consortia can demonstrate how they can use data sources and existing models in combination with innovative approaches and high specification data and technology to achieve an optimal balance of value for money and high performance and relevance of the services they provide.

- Considering the inclusivity of the next digital frontier: The Sustainable Development Goal agenda has a core principle of ‘leave no-one behind’, which includes narrowing the Digital Divide between those that have integrated into a mostly digital-first economy and those that continue to be excluded from it due to poverty and marginalisation. Like the ‘Internet for Development’ and ‘Mobile for Development’ efforts that preceded it, Space for Development needs to consider how the benefits afforded by these new technologies can be realised by as many people as possible.

- GDA can support efforts to establish a strong ethical framework relating to the use of digital data: Transparency and ‘explainability’ in the way that data is collected, processed and stored is a ‘hot topic’ for many digital businesses that are collecting information on the users of their internet and mobile applications. In the case of satellite data, the remote and unobservable collection of data from satellites hundreds of kilometres above the Earth, and the use of models with in-built assumptions and/or possible bias require industry and governments to ensure that practices can be justified, transparently presented and relied upon to protect communities from any harmful repercussions.

As part of Caribou’s Strategic Analysis under the GDA M&E contract, we will continue to monitor the development landscape and through the delivery of an Annual Strategy Roadmap study, we will provide analysis to support ESA’s decisions over the future direction of the GDA programme.

[1] According to the Digital Public Goods Alliance, DPGs include open-source software, open data, open AI models, open standards and open content that adhere to privacy and other applicable laws and best practices, do no harm by design, and help attain the SDGs.