Satellite Earth Observation (EO) data is transforming the development landscape and has received growing recognition in its use for Monitoring & Evaluation (M&E) purposes. The European Space Agency (ESA) Global Development Assistance (GDA) programme recognises EO’s value in M&E and, as part of its M&E and Impact Assessment (GDA M&E) activity, has released a Topical Overview covering this area. In addition, EO for M&E is an integral use case scenario for the upcoming GDA Analytics Processing Platform (APP) as M&E’s cross-cutting nature aligns with the cross-cutting user-oriented software tools that GDA APP will provide to International Financial Institutions (IFIs).

M&E is an essential process to development interventions

Monitoring and evaluation enhance and feed into each other. Monitoring is the process by which data is collected in order to track progress made in an intervention or activity with a view to adjusting and improving that intervention on an ongoing basis. Evaluations are conducted to assess the impacts and results of an intervention. In the context of IFIs, monitoring can be seen as a two-layered approach whereby, on the one hand, the borrower in charge of project implementation carries out the activities linked to the M&E system designed for the project and, on the other hand, the IFI that provided financing performs ‘supervision’ to ensure that the borrower complies with the provision of the financing agreement and the environmental and social standards. M&E considerations need to be integrated from the very beginning of a programme lifecycle, starting with the articulation of the measurement framework itself (i.e. what data is required), the design of data collection processes (i.e. how and when that data will be collected), ongoing monitoring activities, and then post-programme evaluation upon completion.

Development programmes are increasingly subject to public scrutiny putting pressure on IFIs to improve their M&E processes. IFIs have to answer three key questions; (1) how funds are being used, (2) whether funds have been used effectively and (3) whether projects implemented are achieving their intended goals.

M&E at the WB and the ADB

There are three key dimensions when it comes to M&E in IFIs: third party monitoring (TPM), self-evaluations and independent evaluations.

- TPM refers to (i) an approach to smart supervision whereby the IFI contracts an independent agent to verify that project implementation by the borrower complies with the provision of the financing agreement and that the environmental and social performance of the project meets the agreed standards; and (ii) an approach to project implementation whereby the borrower contracts third parties to strengthen monitoring and evaluation systems and obtain additional data on the achievement of progress development.

- Self-evaluation is conducted by those responsible for designing and implementing a country strategy, programme, or project.

- Independent evaluations are conducted independently of management and are passed on directly to the Executive Board. Whilst the WB structures its independent evaluations by work streams (e.g., Gender; Fragility; Conflict and Violence etc), the ADB structures its independent evaluations by evaluation products (e.g., High-Level Evaluations, All Other Evaluations etc).

EO satellites overcome some of the key gaps and shortfalls in traditional data collection in M&E

The value of satellite-derived EO data for M&E can be explained through its key characteristics:

- Affordability: thanks to its remote acquisition, EO data can make TPM and evaluations more affordable, particularly when accessed freely through e.g., the Copernicus Sentinel Satellites).

- Coverage: satellites have global coverage, allow access to remote and conflict areas and are comparable across different countries. The data also enables certain measurements that might otherwise not be possible to obtain “on the ground”.

- Frequency and speed: EO data can be obtained at varying temporal frequencies up to multiple times per day, and can be made available very quickly (i.e. within hours or minutes of observations). This is particularly useful in evaluating projects that are time-sensitive such as agricultural planting timings.

- Objectivity: EO data is less susceptible to biases that may occur from human observations.

- Anonymity: Unlike face-to-face data collection methods, satellites can make observations on the ground without being noticed.

- Continuity: As Tala Hussein, a quality specialist at the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), puts it “in the field, you cannot see the past.”[1] Conversely, some EO data series date back to the 1970s, enabling observations to be made to the same area of interest over a longer time period in order to monitor changes over time.

Enhancing M&E by leveraging EO data in IFIs

Our report provides several examples of how both the WB and the ADB have leveraged EO data to enhance their TPM and evaluation activities in developing countries.

For example, with the aim of enhancing regional trade, investment and connectivity in Central Asia, the WB has used EO to observe peri-urban landscape of inland markets over an extended period of time as a proxy to estimate current and past levels of informal trade.

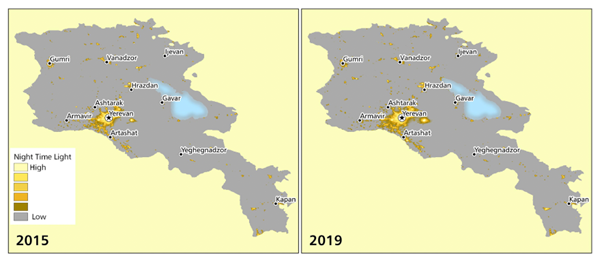

We also found examples of where the ADB is using satellite EO data for its M&E activities. For example, in the North-South Road Corridor Investment Programme in Armenia, the ADB is using night-time lights (NTL), as a proxy for how the new road has impacted economic activities over time.

We are seeing at least a base level of awareness of the value of EO for M&E. However, not all projects are suited to EO-enabled M&E, as explored below.

Unlocking the power of EO data for M&E in development operations

The nature of remote sensing means that it lends itself most to tracking observable changes in physical features such as forestry mapping or changes to urban infrastructure. As shown above, satellites can also provide insight into changes in economic activity, such as through the observation of night-time lights which are a proxy for human activity.

However, there are some limitations to the use of EO for M&E. For instance, from a thematic perspective, there are certain types of development intervention where a more nuanced understanding of changes to societal structures or human development may be required and such changes cannot be observed using EO data. There are some changes – such as socio-demographic issues – that a satellite simply cannot see or approximate due to their lack of a visible trace in our physical environment.[2] In these situations, EO data may be less useful. Additionally, there are methodological constraints that need to be considered when collecting data remotely for M&E purposes. The ability to gather data and feedback on development interventions through interviews and ‘on the ground’ presence is often unparalleled and its importance should be considered before opting for a fully remote data gathering process. In many cases, face-to-face contact and localised data collection are still key in monitoring and evaluating interventions and building capacity “from the ground up”.

“Satellite data helps get eyes on the ground where we cannot always have feet on the ground. Yet, often in-field insights and face-to-face engagement with local stakeholders are crucial, to ‘ground-truth’ assumptions and get details to evaluate interventions that can just not be captured by an image taken from far away.”

Bernhard Metz, Founder and Programme Manager of the Geo-Enabling Initiative for Monitoring and Supervision (GEMS)

The GEMS launched by the World Bank is trailblazing an approach to M&E that leverages geospatial information by building capacity in digital data collection and analysis with government agencies and development practitioners. Through this, a large community of enumerators collect ground-level data to complement any satellite-derived information. GEMS has built up an impressive level of awareness across the WB and will be a strong partner for ESA as it seeks to promote greater uptake of EO data for M&E of development finance interventions.

Through the upcoming GDA APP, ESA will be able to demonstrate the feasibility and potential benefits of using EO data for M&E purposes. As the volume of case study examples increases, however, it will also be important for IFIs to share the value and learnings of using EO for M&E with others to promote further mainstreaming.

The report is available here. Please contact gda@esa.int with any questions.

[1] United Nations Institute for Training and Research, ‘Using earth observation and GIS for the monitoring and evaluation of development projects’, https://unitar.org/about/news-stories/news/using-earth-observation-and-gis-monitoring-and-evaluation-development-projects

[2] O’Connor B., Moul K., Pollini B., de Lamo X., Simonson W. (UNEP-WCMC), Compendium of Earth Observation Contributions to the SDG Targets and Indicators, 2020, https://eo4society.esa.int/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/EO_Compendium-for-SDGs.pdf

![[VIDEO] Earth Observation for Environmental, Social, and Governance Schemes](https://gda.esa.int/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/image001-340x250.png)